New gene-editing tool could cure disease. Or customize kids. Or aid bioterrorism.

Some of the greatest benefactors of our species are not the recognized do-gooders but those paid to satisfy their curiosity: the scientists. Such pure and unsullied inquiry has yielded thousands of valuable byproducts, including antibiotics, vaccinations, X-rays and insulin therapy.

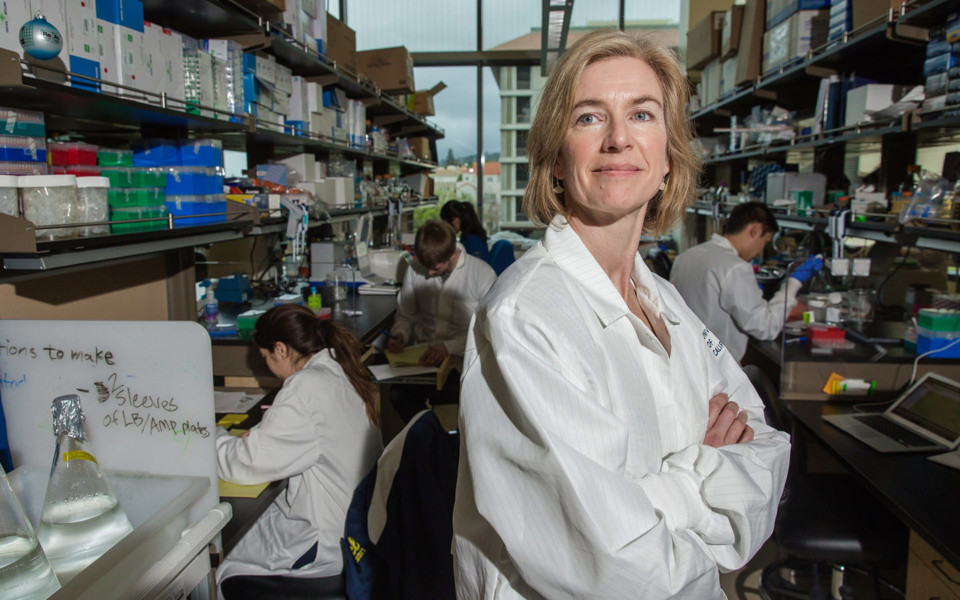

Jennifer Doudna and Samuel Sternberg’s “A Crack in Creation” describes another fortuitous discovery, a method that promises to revolutionize biotechnology by allowing us to change nearly any gene in any way in any species. The method is called CRISPR, pronounced like the useless compartment in your fridge. In terms of scientific impact, CRISPR is right up there beside the double helix (1953); the ability, developed in the 1970s, to determine the sequence of DNA segments; and the polymerase chain reaction, a 1980s invention that allows us to amplify specified sections of DNA. All three achievements were recognized with Nobel Prizes. CRISPR — developed largely by Doudna and her French colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier — also has a strong whiff of Nobel about it, for its medical and practical implications are immense.