Pondering ‘what it means to be human’ on the frontier of gene editing

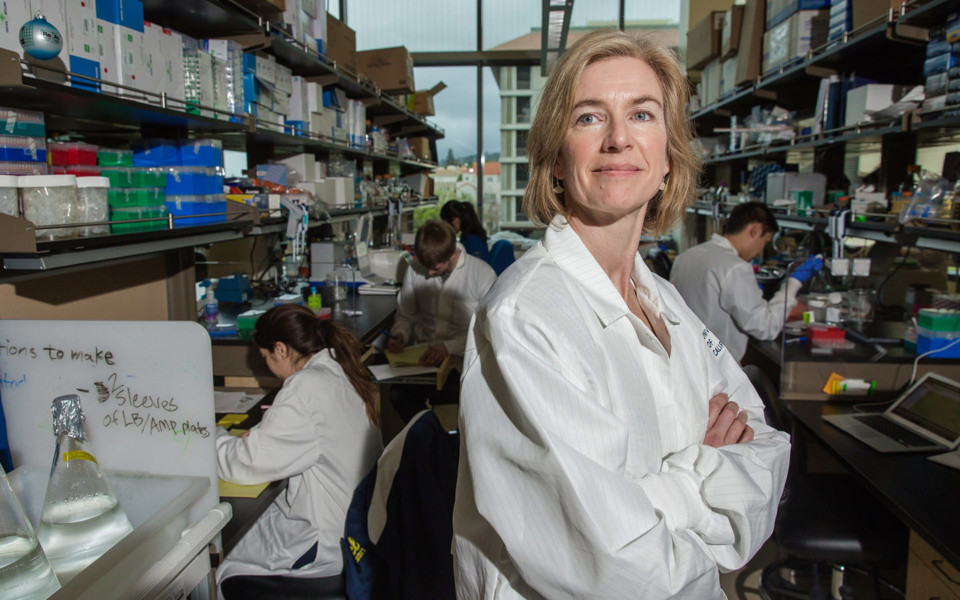

People in pain write to Jennifer Doudna. They have a congenital illness. Or they have a sick child. Or they carry the gene for Huntington’s disease or some other dreadful time bomb wired through every cell in their body. They know that Doudna helped invent an extraordinary new gene-editing technology, known as CRISPR.

But they don’t all seek her help. One woman, the mother of a child with Down syndrome, explained: “I love my child and wouldn’t change him. There’s something about him that’s so special. He’s so loving in a way that’s unique to him. I wouldn’t change it.”

The scientist tears up telling this story.

“It makes you think hard about what it means to be human, doesn’t it?” she says.

Doudna (pronounced DOWD-na) has been doing a lot of hard thinking lately as she ponders the consequences of CRISPR.

The world of molecular biology is mad for this new form of genetic engineering. Scientists have turned a natural bacterial defense system into a laboratory tool for cutting or reordering genes in a cell — an innovation that could be used to target genetic mutations linked to numerous diseases.

CRISPR is not the first method for manipulating genes, but it’s by far the cheapest, easiest, most versatile. Its many attributes have generated incredible excitement as well as apprehension. While the approach hasn’t been applied yet in humans for therapeutic purposes, that’s on the horizon. So are worrisome scenarios involving genetic enhancements and purely cosmetic applications…